Setting the context

EUDR and legality due diligence

The EU Deforestation-Free Regulation (EUDR) has fundamentally upended the way commodity traders must approach sourcing and supply chain compliance. What was once an optional or good practice — checking shipments for alignment with conservation laws — will become a strict legal mandate.

Soon, every ton of soy, every kilogram of cocoa, and every shipment of palm oil must come from land that is proven to comply with protected area legislation in its country of origin.

Deforestation and Conversion-Free commitments

Deforestation- and Conversion-Free (DCF) commitments are increasingly shaping corporate supply chain management frameworks. Although still voluntary, these commitments are subject to growing scrutiny from investors, buyers, and civil society. Unlike the EUDR, which is legally focused on compliance with forest protection laws, DCF extends to land conversion, ensuring sourcing avoids not only deforestation but also the destruction of other critical ecosystems, such as grasslands, peatlands, and savannas.

The protected areas challenge

Protected areas inject significant complexity and uncertainty into due diligence. Unlike blanket prohibitions, most protected areas allow specific uses and recognise the role of smallholder communities, who often act as de facto land stewards.

There are strictly protected areas where no agricultural development is permitted, and sustainable-use areas that allow regulated activities under specific conditions.

The level of permitted activity directly affects the complexity of compliance verification, as sustainable-use areas require detailed assessment of land titles, local authorisations, and management practices.

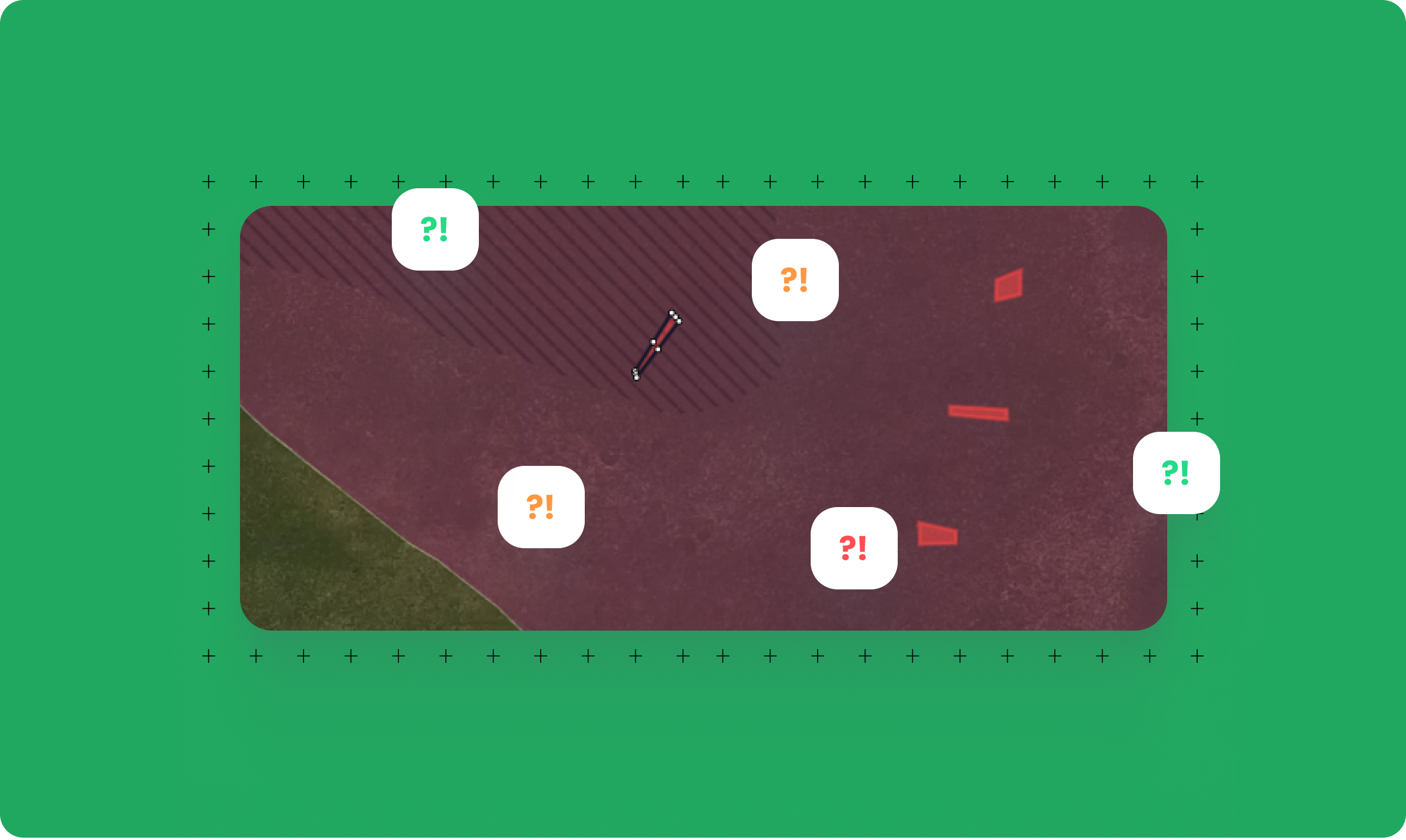

Procurement and sustainability teams face tough, time-consuming questions. The challenge is not simply “Is this plot inside a protected area?” but “Is farming legally allowed here, under what conditions, and how can this be proven for regulators?”

Each unresolved or ambiguous case delays shipments, disrupts supply chains, and may restrict access to essential raw materials, resulting in significant financial impact and risking livelihoods.

Direct impact: farms, cooperatives, and supply risk

The effect of rigid or poorly interpreted protected areas compliance is not theoretical. Protected areas contribute to ecosystem connectivity, biodiversity conservation, water regulation, and climate change mitigation. They are critical for maintaining ecological services and reducing deforestation-linked carbon emissions.

Blanket exclusions can disqualify hundreds or thousands of farms, with direct consequences for farmers and the cooperatives that depend on stable, long-term relationships. Exclusion from supply chains reduces income stability, limits access to markets, and may jeopardise the long-term viability of family-run or community farms.

As environmental factors already constrain supply, further uncertainty about farm status in protected areas could push supply chains into crisis, while undermining rural incomes and organisational trust.

Why “protected area” does not equal “prohibited area”

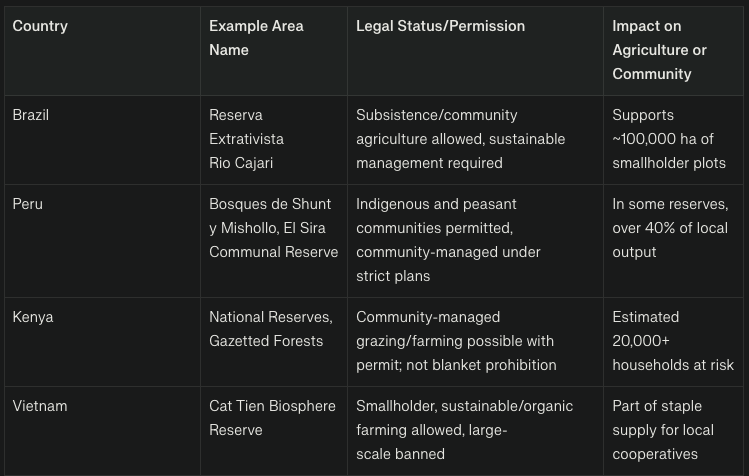

Most countries balance conservation with community well-being. For example:

- In Brazil, reserves like the Reserva Extrativista Rio Cajari and various Sustainable Development Reserves explicitly permit community-managed, smallholder agriculture, subject to sustainable management plans and local council oversight. High-impact activities are banned, but traditional agriculture and subsistence farming are protected.

- In Peru, Communal Reserves and Regional Conservation Areas support indigenous and peasant community farming, provided that resource use aligns with conservation goals and that approved management plans are in place.

- Kenya’s National Reserves and Gazetted Forests may permit regulated community uses, including grazing or agriculture, which often require permits or community management, along with restoration obligations.

The role of IBAT

The Integrated Biodiversity Assessment Tool (IBAT) is emerging as the compliance backbone for protected area due diligence. It is an alliance of four of the world’s largest and most influential conservation organisations: BirdLife International, Conservation International, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC).

IBAT offers authoritative, government-validated maps that integrate the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA), recognised by regulatory bodies worldwide. When auditors ask about data sources, IBAT’s 66-year legal record provides unmatched credibility.

Critical gaps: legal permissions are not always in the data

However, experience shows IBAT and even protected area (PA) data rarely tell the full legal or operational story. Most datasets focus on boundaries and management categories, but omit detailed permissions—who can farm, under what restrictions, and how policy is changing.

Legal farming is possible in many “protected” polygons, but verifying and documenting these exceptions can stall compliance by weeks or months.

Case examples: legal farming in protected areas

These permissions are crucial for secure sourcing and protecting livelihoods. In some regions, excluding all PA-linked producers would remove over 20% of the total supply, disproportionately impacting smallholders and risking the collapse of cooperative networks.

Meridia’s enhancement: clarity for action

The IUCN provides a standard classification for protected areas from IBAT, ranging from Categories I to VI, as well as areas without an assigned IUCN category. While this classification offers a useful baseline, it does not fully capture the nuances of local legal frameworks or permitted land uses.

To address this, Meridia’s Verify methodology has been to conduct a manual review and categorisation of all protected areas, taking into account the specific legal context and the conditions under which agricultural activities may be permitted.

During this process, all categories of protected areas are reviewed and researched to assign a risk of non-compliance with agricultural land use legality that is connected to actual laws and legal frameworks – an important detail the IUCN category system does not capture.

Under our methodology, we’ve identified four broad categories to classify agricultural permissions within protected areas:

- No agricultural activity is permitted (critical risk)

- Agricultural activity is allowed only under specific conditions (critical risk)

- Protected area, but with exceptions for sustainable agricultural use and aligned with conservational goals (medium risk)

- Protected area, but with general agricultural permissions, or not a legally protected area under national law (low risk)

Each category is designed with mitigation plans and resolution steps to make further due diligence and a final risk assessment straightforward with your local suppliers.

Real-world impact

- In pilot countries, actions to clarify protected area permissions have resolved the risk status for thousands of farm plots in Verify, reducing unnecessary exclusion and supply disruptions.

- Enhanced IBAT has changed risk scores in some supply chains from >30% “uncertain” to <5%, releasing material volumes for legal trade and safeguarding farmer incomes and cooperative stability.

Recommendations for compliance teams

- Don’t rely solely on default PA boundaries. Always seek legal context for each polygon: what is the explicit agricultural permission, and can smallholder or cooperative use be proven legal?

- Use IBAT as the regulatory gold standard, but supplement with locally validated legal analysis whenever possible.

- Quantify and communicate the supply and livelihood impact of exclusion—engage buyers and regulators with real data to avoid unnecessary harm.

- Invest early in proactive clarification of farm status to avoid costly shipment delays at the point of export.

By approaching protected areas as nuanced legal spaces rather than imposing blanket prohibitions, and utilising tools that combine authoritative data with legal review, compliance becomes more predictable, defensible, and equitable for all supply chain actors.

.png)